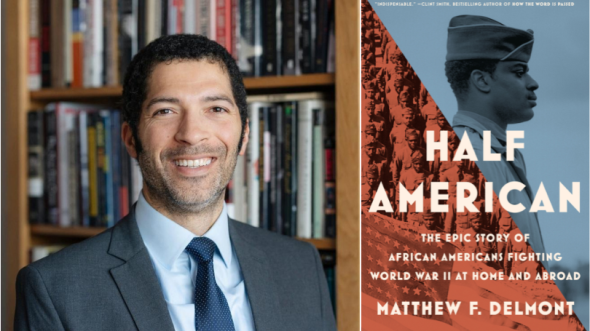

Professor Matthew Delmont has engaged thousands of high school teachers in exploring the history of the World War II era from the perspective of Black Americans.

Since Half American: The Epic Story of African Americans Fighting World War II at Home and Abroad was published in October, author Matthew Delmont has received praise from such outlets as PBS, NPR, and the New York Times for bringing to light Black Americans' heroism during the war and experience of racism.

But one response to the book left him "completely amazed and blown away."

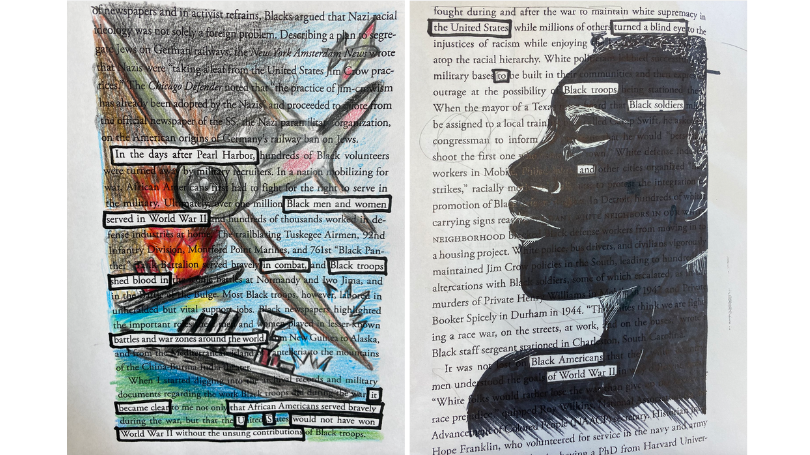

Students at Eleanor Roosevelt High School in Eastvale, Calif., listened to and read the book's introduction and were asked by their U.S. history teacher, Amanda Sandoval, to create "blackout poetry" that captures a "big idea" that others should know about. They were tasked with selecting a page, circling words that relate to their idea, and sketching a design or image that supports their poem or statement.

Sandoval shared eight submissions from the class on Twitter, where Delmont saw them. (She also shared a link to her assignment.)

"One of my students' biggest takeaways from Matt's book was that they did not realize how many obstacles African Americans had to overcome to even participate in the war effort," Sandoval says. "The fight against racism that was pursued during the war years laid the foundation for the civil rights movement in the coming decade. When teachers bring histories like those that Matt highlights in his book to the forefront, it strengthens students' understanding of American history as a whole and even leads to a better understanding of the present."

"I was so impressed with the creativity of the students, and how they transformed the book in entirely new ways," says Delmont, the Sherman Fairchild Distinguished Professor of History. "They truly helped me see my own book in ways that I hadn't anticipated."

Delmont had donated 2,500 copies of his book to teachers across the country, including Sandoval's class. Delmont partnered with the Zinn Education Project (coordinated by Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change) to reach out to teachers and distribute the books.

Half American is Delmont's first trade book, and he wrote it with "everyday readers" in mind.

"I think this is similar to how I try to teach," he says. "When you have students in the classroom, you want to talk in a narrative fashion because people respond positively to stories."

With critical race theory and the College Board's new AP course on African American studies mired in political controversy, Delmont feels a sense of urgency to correct "a fundamental misunderstanding of what it means to study history."

"I'm so excited to share the book with students and teachers and convey that studying history is about understanding evidence, and really putting those puzzle pieces together in ways that help us get a better understanding of the past. This is what gets lost in contemporary political debates," he says.

"It's important for students to be able to grasp that there is methodology for studying history, and that through careful, detailed attention to primary sources you can get a more nuanced understanding of any historical event. You can develop a toolkit, so to speak, of what it means to think like a historian, and apply it to any moment in history."

'A Morale, and an Intellectual, Boost' for High School Teachers

In addition to donating thousands of books, Delmont also took part in a Nov. 2 webinar for K-12 teachers as part of the Zinn Education Project's Teach the Black Freedom Struggle series. (A recording of the class can be watched online.) In each session, a teacher interviews a historian and breakout rooms allow participants to discuss the content in small groups and share teaching ideas. In conversation with fellow historian Jeanne Theoharis, Delmont dismantled some common myths about America and World War II and illuminated their damaging effects.

For example, a well-worn World War II narrative celebrates the unity of Americans in the face of fascism—but there were deep divisions across the county, especially regarding race. In 1943 alone, Delmont said, there were more than 240 race riots or clashes across the country.

"If we look back and think that World War II was a simpler time, or a more peaceful or unified time, it makes it seem like protests around racial justice today are surprising, or that they've come out of thin air," Delmont said. "If you tell the actual history about what happened in World War II, it's clear that these battles have been going on for generations. Part of the urgency of the Black Lives Matter movement in the last decade is that people's grandparents were fighting these same battles in these same streets, going back to World War II and earlier."

The Zinn Education Project hosted a follow-up curriculum workshop with teachers a few weeks after the webinar. Delmont provided the group with numerous primary source documents, and teachers brainstormed ways to incorporate them into their teaching.

"Matt's generosity was such a gift to teachers," says Deborah Menkart, co-director of the Zinn Education Project and executive director of Teaching for Change. "With teaching through the pandemic and then being attacked for what they're teaching, it's been a particularly hard time for many public school teachers. Not only did they appreciate getting the book, but they also appreciated that a scholar was investing in them. It was a morale, and an intellectual, boost."

The Zinn Education Project collected feedback from teachers about their request of Delmont's book for their classrooms. Many pointed to the lack of resources available to them for understanding and exploring the African American experience of World War II.

"Because when I teach WWII, the textbooks often relegate the contributions of African Americans to a paragraph or one page," a teacher from Maple Glenn, Penn., wrote. "I know there is so much more to know and I want my students to have this knowledge. I need to educate myself because unfortunately, my own education was lacking about the contributions of African Americans to WWII."

"I have embedded Black history throughout the curriculum but have found it difficult to find sources that complicate the narrative of Black soldiers in World War II," a teacher from New Jersey wrote. "Most of the sources that my district has provided put forward a simple patriotic narrative that 'Black soldiers contributed to the war effort.' This narrative is incomplete and does not make a clear connection between the fascism abroad and the racism experienced at home."

Delmont says he especially loves working with teachers because of the "scaling effect." "You know the teachers will take the information and then share it with at least 30, potentially 100 students each year," he says.

"And it's so inspiring to see teachers like Amanda, who are committed to helping young people understand the world and tap into their own creativity and brilliance."