In his critically acclaimed new book, history professor Matthew Delmont highlights the vital role that Black Americans played in the Allies' victory—and their courageous efforts back home in the fight for civil rights.

When Matthew Delmont was poring over World War II–era newspaper clippings several years ago for a book project about the lives of Black Americans in the 1930s and '40s, he realized that there were dozens—even hundreds—of stories about their assisting with the war effort.

"These weren't famous figures in any way," says Delmont, an expert on African American history and the civil rights movement. "They were just everyday people from different neighborhoods who had been drafted or had volunteered to be in the Army, Navy, Marines, or Women's Army Corps."

Struck by the volume of the profiles and their stories of courage, Delmont set out to explore World War II from the perspective of African Americans. "It's one of the things I like most about being a historian," Delmont says. "There are always more aspects of the past that remain to be discovered, and there are new approaches we can take. For me, it was just so exciting to try to bring more of these stories to the foreground and try to really put the puzzle pieces together in new ways."

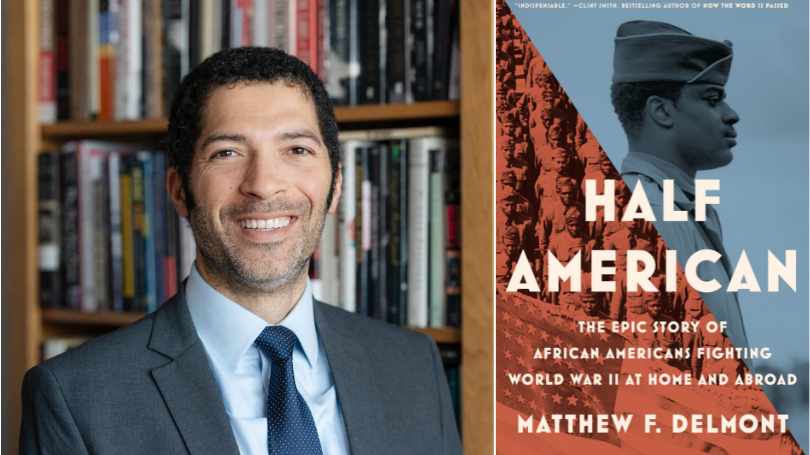

Delmont's critically acclaimed new book, Half American: The Epic Story of African Americans Fighting World War II at Home and Abroad, illuminates some of the crucial yet unsung contributions of the more than 1 million Black men and women who helped win World War II—and their efforts back home to fight for civil rights. The book is a New York Times Book Review editor's choice and has received starred reviews from outlets such as Publishers Weekly, Library Journal, Kirkus Reviews, and Booklist.

Delmont has discussed the book on NPR's Fresh Air, ABC News, Washington Post Live, and WBUR's On Point.

At Dartmouth Delmont serves as the Sherman Fairchild Distinguished Professor of History and the associate dean for interdisciplinary studies. The recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship and National Endowment for the Humanities Public Scholar Award, he is the author of four previous books and regularly shares his research with major media outlets such as The New York Times, NPR, and The Washington Post.

In a Q&A, Delmont discusses some of the surprises he encountered in his research for the book, and the chapter that was hardest to write.

You've noted that many of these stories of Black contributions to the war effort have been previously untold but represent critical pieces of history. What are some of these efforts you want more people to know about?

One I would highlight was the important role that Black troops played on and after D-Day, which was a crucial turning point in the war. There were about 1,700 Black soldiers who were part of that D-Day invasion of the beaches in Normandy, including a barrage balloon battalion. Barrage balloons were these large, helium-filled balloons that were tethered to ships or held on the shore and floated hundreds of feet in the sky with mines dangling from them. They would keep Nazi planes from being able to drop to lower altitudes where they could strafe the beaches. The 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion comprised all African American soldiers. So they played an important role in the D-Day invasion, protecting the ships as they crossed the channel and then protecting the beaches the day after the invasions.

But I think Black troops played an even more important role in those months after the D-Day invasion, because they were really the backbone of the American military's logistic and supply forces. The gear of the troops, ammunition, tanks, and trucks that were transported across the English channel after D-Day were moved by Black troops. They were loading and unloading ships. They were doing the supply work that really facilitated the fight after D-Day. And the group that became particularly important in that aspect was a group of truck drivers called the Red Ball Express; 75% of those truck drivers were Black soldiers.

These Red Ball Express truck drivers made the American military the most mobile force in the war. It's what facilitated the Allies being able to eventually defeat the Germans. This was really an important battle of supply—and, if you take that perspective, Black troops were absolutely vital not only to the success of D-Day but also to the war effort more broadly.

Was there anything that particularly surprised you in your research for this book?

I think two things surprised me most. One was the really important supply role that Black troops played in the war. It's not an argument I anticipated making when I started the book, but I truly believe that the American military and the Allies could not have won World War II without the contributions of Black troops. I think that forces us to think differently about what World War II was about: It wasn't just a battle of strategy and will, it was a battle of supply. Black Americans were often in unglamorous logistic and supply roles, but those roles were really vital to winning the war. I think that was the first big surprise.

The second surprise was how much Black veterans contributed to the civil rights movement. I knew that there was a continuity between the work that Black veterans did during the war and how many became involved with civil rights afterwards. But the scope of it was much vaster than I previously understood. That surprised me as well.

You mention that the "homecoming" chapter, in which you discuss the return of Black veterans from the war overseas, was one of the hardest for you to write. Why is that?

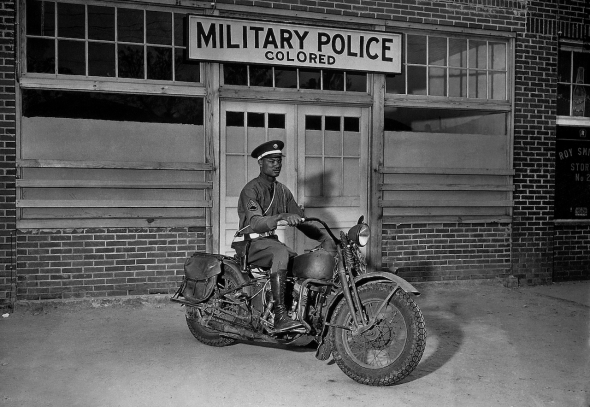

I talk about the really hostile reception that Black veterans received when they came back to the United States. It's there that you can see clearly how World War II meant something very different for Black Americans than it did for white Americans. For a lot of white Americans, what they wanted was to return to the way things were before the war. But for most black Americans, that was exactly the opposite of what they wanted. They didn't want to return to a country that treated them as half American. They didn't want to return to Jim Crow segregation in the South, to discrimination in schools and employment. They didn't want to return to a country where police brutality and lynching were the norm. And so, for Black veterans, they come back, and they immediately start fighting for civil rights. But they also run up against a lot of white communities that don't want to see freedom and democracy for Black citizens.

The book covers more than a dozen examples of Black veterans being lynched or attacked largely because they were veterans and because they were demanding equal access to voting and to other rights. The country was not unified in a belief that Black Americans deserved and had earned equal citizenship.

The other piece of that story is the way that the GI Bill was executed, which had a discriminatory impact for Black veterans. The GI Bill was the main policy that enabled veterans to enter the middle class and to get readjusted to life in the United States. For most white veterans, it's what helped propel them into middle class status and really helped to set up their families and future generations for success. For too many Black veterans, they were denied their GI Bill benefits because the benefits were distributed at the local level. The VA offices, particularly in the South, could prevent Black veterans from being able to access job and education benefits. And then the mortgage industry discriminated against Black veterans as well, so the VA-backed mortgages that were offered to veterans weren't accessible by Black veterans in the same way.

The title of the book is drawn from a letter written by a young Black man in Kansas facing the draft for World War II. Why was it so meaningful?

James Thompson, a 26-year-old from Wichita, Kansas, wrote a letter to the Pittsburgh Courier, which is an influential Black newspaper. This was in late December of 1941, after Pearl Harbor, when he knew that he and other Black Americans were going to be drafted. What he asked in the letter was, "Should I sacrifice my life to live half-American?" He goes on to ask a number of other questions, such as "What does it mean to serve in a country that doesn't treat me as a full citizen? What does it mean to serve in a segregated military?"

James Thompson's letter is what helped spark the Double Victory Campaign, which was the rallying cry for Black Americans during World War II and meant victory over fascism abroad and victory over racism at home. His words really stuck with me as I worked on this book. And I think that phrase, "Half American," speaks volumes about what the war looked like for Black Americans.

READ MORE